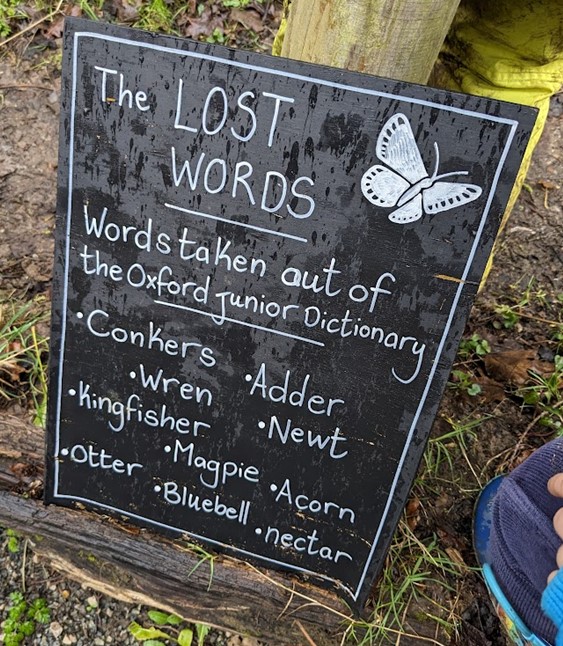

Recently, one of us was walking through a Wildlife Trust nature reserve when we came across the sign you can see in the image above, about words that have been removed from the Oxford Junior Dictionary. Around 50 words connected with nature were taken out in 2015 and replaced by words like “broadband” and “cut and paste”. At the time 28 authors, including Margaret Atwood and Michael Morpurgo, wrote an open letter to Oxford University Press pleading that the next edition reinstated the words, but as yet to no avail. Two of the signatories, Robert Macfarlane and Jackie Morris, went on to publish The Lost Words: A Spell Book in response. It’s a book of spells based on each of the words removed from the Oxford Junior Dictionary, with the word “spell” rather than “poem” used to evoke the idea that by virtue of saying the spells, they will be “conjured back to importance”.

The sign about the Lost Words got us thinking (again) about young children’s engagement with nature. Have these natural words been removed because they are no longer important to children? The dictionary is aimed at those from the age of 6; we imagine that by then many children have had experiences like jumping in puddles, climbing on tree stumps and marching through leaves. We also know that these kind of outdoor experiences are important for children’s development. But what about younger children, for instance those from birth to two? What do we know about their opportunities and experiences outdoors?

When it comes to thinking about young children’s opportunities to engage with the outdoors and nature, we have found that it’s children from birth to two who are generally excluded from policy, practice and research. We’ve written blog posts about this before, for instance where we considered the limited amount of research that’s been conducted exploring how children two and under engage with the outdoors when in Early Childhood settings and how a lot of the papers that talk about young children (0-2s) were more concerned with the older children in this age group. We’ve also considered how our research has led us to consider different cultural practices, such as the practice of putting babies to sleep outdoors. Our very latest Froebel Trust funded report, From Weeds to Tiny Flowers: Rethinking the Place of the Youngest Children Outdoors, examines more of the research that’s been conducted on outdoor practices with very young children and offers some new insights into different cultural and geographical practices.

You might be wondering why we’ve used the metaphor of weeds to talk about young children – it doesn’t seem very complimentary! However, this is a term that we have borrowed from the work of Jenks (2005) who uses it to illustrate how children are often viewed like “garden weeds” when they are somewhere they shouldn’t be, or “out of place”. This is easily relatable to very young children, who are seen as “out of place” outdoors because it is perceived as being an exciting space for mobile children to do all the things we mentioned earlier – jumping in puddles, climbing onto tree stumps and marching through leaves – and at the same time perceived as a dangerous space for those who are too young to engage in the environment in that way.

In our review of the literature, we noticed that very young children are likely to be excluded from outdoor spaces, but there are other factors that interact with each other and lead to even more issues of exclusion on the grounds of class, socio-economic status and culture. We also noticed that there are certain voices who talk about outdoor practices with very young children – predominantly from Europe and North America. Other voices are being excluded from the conversation. So now, we are interested to find out how other cultures speak about being outdoors, what their outdoor pedagogies are for very young children, and what we can learn from them.

This finding has informed the piece of research we are working on presently. We are intending to talk to parents from a range of cultural backgrounds to learn about their experiences with their children outdoors whilst living in an urban setting in the UK. We will update you as we progress with our findings.

In the meantime, do please have a look at our lovely FREE OpenLearn course which is based on our research up to this point and focuses on very young children’s opportunities to be outdoors and in nature.